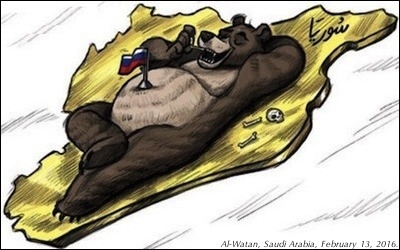

To hear officials in Moscow talk about the war in Syria, you'd think it was a coming-out party for Russia's armed services and military-industrial complex. The two-and-a-half year military campaign has "demonstrated the power of our army and navy ... [and] the tradition of reliability and effectiveness of Russian weapons," President Vladimir Putin boasted in a recent speech. Customers "are coming to us from many directions to purchase our weapons," says Vladimir Shamanov, the head of the Russian Duma's defense committee.

To be sure, the Kremlin's first major far-abroad expeditionary campaign is a stark reminder that its inheritance of Soviet military might is not thoroughly spent, and Putin has clearly made good use of a defense budget comprising just 11 percent that of the United States. But Russia's military performance has underwhelmed most informed observers, and the growth of Russian arms exports has stagnated since Russia's intervention began in September 2015 (rising only from $14.5 billion that year to $15.3 billion in 2017, after tripling over the previous decade). "We don't see any tangible effect of the Syria campaign on Russian defense exports," concluded Sergey Denisentsev of the Moscow-based Center for Analysis and Technology last year.

Russia's military performance in Syria has underwhelmed most informed observers. |

While Russian officials claim to have combat-tested some 215 advanced weapons systems in Syria, often releasing videos to show them in action, we don't really know how most of them performed. In contrast to CENTCOM, the Russian military doesn't release detailed open-source information about airstrikes.

What little information the government makes available is primarily promotional, and often at odds with independent reporting. Four of the 26 cruise missiles fired at targets in Syria from Russian warships in the Caspian Sea in a widely-touted October 7, 2015, launch (timed to commemorate Putin's birthday) are known to have landed in Iran, but Russian officials adamantly denied it.

|

| Admiral Kuznetsov failed to impress. |

Another epic fail they don't like to talk about in Moscow is the three-month deployment of Admiral Kuznetsov, Russia's only aircraft carrier, off the coast of Syria in 2016. The vessel "belched smoke like an old-timey English factory," in the words of military aviation expert Gary Wetzel, and two aircraft were lost attempting to land on it before Admiral Kuznetsov returned home for a two-and-a-half year refit.

Interestingly, Putin's praise of Russian weapons usually carries the curious note (e.g. here and here) that any and all defects uncovered during combat trials will be fixed — suggesting keen awareness that too many Russians serving in Syria have experienced equipment failures for unqualified boasts to be taken seriously by the public. Russia has lost of up to thirteen fixed-wing aircraft and five helicopters to hostile fire and accidents.

As impressive as footage of Russia's cutting-edge Su-34 strike fighter hitting targets with guided missiles may be, the overwhelming majority of sorties have been flown by older-generation Su-24 and Su-25 aircraft dropping unguided munitions from high altitudes. This is partly for practical reasons. The vast majority of these aircraft aren't fitted with targeting pods for precision attacks. Moreover, "lacking in the ISR [intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance] assets necessary to conduct information-driven combat operations," according to a new report on Russia's military performance by Michael Kofman and Mathew Rojansky, the Russian Air Force couldn't make very effective use of guided munitions in Syria even if it were so equipped. "Advanced capabilities are superfluous on a routine Russian sortie over Syria, which consists of dropping tons of explosives on hospitals and bakeries," British journalist Anshel Pfeffer wryly notes.

In fact, the Russian Air Force appears to have deliberately employed the same types of "dumb" bombs in use by its Syrian counterpart so as to confound war crimes investigators. "I suspect they want to use those munitions because it makes attribution more difficult," said one UN official.

Moscow's reluctance to operate advanced aircraft in Syria may also reflect security concerns. Putin has insisted on keeping the Russian footprint in Syria small, just 4,000 or so uniformed Russian servicemen — inadequate to guarantee the security of an air base in the middle of a civil war. On December 31, 2017, a rebel mortar attack on Hmeimim air base reportedly damaged or destroyed seven Russian aircraft. A sophisticated rebel drone attack on the base in January miraculously damaged no aircraft.

It doesn't take much practice to indiscriminately target civilians. |

This isn't to say that there haven't been benefits to the deployment. Combat testing of new weapons systems is always valuable, even — indeed, especially — when the results leave much to be desired. Moscow has rapidly rotated troops and commanders in and out of Syria, giving a taste of combat experience to a wide pool of both. But it doesn't take much practice to indiscriminately target civilians.

Gary C. Gambill is a Philadelphia-based policy analyst. Follow him at Twitter and Facebook.