We'll probably never know exactly why Syrian President Bashar Assad ordered Saturday's chemical weapons attack on the encircled rebel-held city of Douma with pro-regime forces on the eve of complete military victory.

But this much is certain: Russian President Vladimir Putin is the big loser.

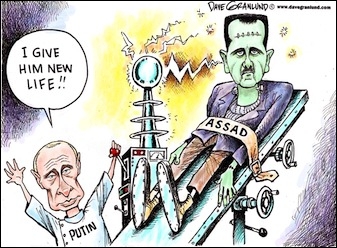

The Russian leader has far outpaced his Soviet predecessors in going to bat for Syria's Assad regime – including two-and-a-half-years of air strikes against its enemies and use of Russia's Security Council veto twelve times, in the words of Amnesty International, "to shield the Syrian government from the consequences of war crimes and crimes against humanity." And yet he can't seem to get his client to do what he wants when it really counts.

What Moscow really needs now is an internationally-endorsed political settlement that preserves and rebuilds the Syrian state apparatus, as regional and international buy-in is necessary to finance the country's estimated $200-300 billion reconstruction tab. Toward this end, it has reached understandings with the rebels' primary sponsors, Saudi Arabia and Turkey, to ensure that some representation of a Sunni Arab "opposition" will acquiesce to Assad's continued rule. All Putin needs is for the Assad regime to avoid gratuitous bloodshed and consent to modest constitutional changes.

Putin can't seem to get his Syrian client to do what he wants when it really counts. |

Time and again, however, Moscow has shown it lacks sufficient leverage over pro-regime forces to compel respect for ceasefires brokered by its own diplomats. Five weeks ago, Russian envoys spent three days haggling over the wording of United Nations Security Council Resolution 2401, which mandated a 30-day cease-fire to allow for humanitarian deliveries and medical evacuations. But Assad's UN envoy immediately shrugged off the resolution, and his air force persisted with the devastating daily bombardment of rebel-held Eastern Ghouta in suburban Damascus that the Security Council had been working so feverishly to stop. A December 2016 ceasefire negotiated at the highest levels with Russia was scuttled by pro-regime forces on the day it was supposed to go into effect.

It's no mystery why this happens. With Syria's military depleted by defections and casualties, pro-regime forces on the ground are today dominated by an estimated 30,000 foreign (mostly Lebanese, Iraqi, Afghani, and Pakistani) Shi'a fighters under the control of Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) commanders. In addition, Iran finances and exerts substantial operational control over many native Syrian militias operating alongside Assad's military.

Assad owes what's left of his throne primarily to Iran, not Russia. |

Outgoing National Security Advisor Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster's recent estimation that, all told, Iranian proxies comprise 80 percent of pro-regime forces is probably a bit high, but such lopsidedness is certainly evident among assault forces fighting for the regime. Hundreds of soldiers taking part in the final assault on rebel-held east Aleppo were outnumbered by some 5,000+ foreign Shi'a fighting alongside them. The force that captured the strategic border town on Abu Kamal last October was reportedly composed almost entirely of non-Syrians under IRGC command. Although Assad is appreciative of Russian air power, he owes what's left of his throne primarily to Iran, not Russia.

While Moscow and Iran share the short-term goal of eliminating insurgent threats to the Assad regime, the latter has wholly different long-term objectives – maintaining proxy control of a contiguous corridor of territory from its border crossings into Iraq to the Golan Heights and the Mediterranean Sea and building a "resistance" infrastructure in Syria for confronting Israel. Since any negotiated political settlement can only serve to constrain its freedom to maintain and expand this infrastructure, Iran is determined to prevent serious peace talks.

Russia's inability to extract credible commitments from Assad has fatally undercut its impressive diplomacy. |

Russia's inability to restrain and extract commitments from its Syrian clients has fatally undercut its otherwise impressive diplomatic efforts to broker a regionally-sanctioned resolution of the Syria conflict. Most major Sunni Arab and Kurdish factions steered clear of Putin's much-touted "Syrian National Dialogue Conference" at the Black Sea resort of Sochi in January. Somehow Russian Foreign Minister Sergey V. Lavrov still managed to get heckled while addressing the rump assembly of pro-Assad delegates.

For Putin, Assad's latest chemical weapons attacks couldn't have come at a worse time — right after President Trump's abrupt declaration that U.S. troops would leave Syria "very soon" and "let the other people take care of it" threw U.S. policy into chaos. A harsh reality is surely setting in at the Kremlin: Putin has staked Russia's claim to be a global power on the fate of a brutal Iranian client regime forever stigmatized by its responsibility for hundreds of thousands of deaths, and over which he cannot exert decisive influence.

Gary C. Gambill is a Philadelphia-based policy analyst. Follow him at Twitter and Facebook.