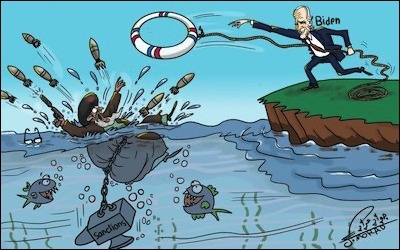

The State Department's announcement Tuesday of a sanctions waiver that will allow Iran to access blocked funds in Japan and South Korea was the latest in a string of decisions indicating that President Biden's foreign policy team is afflicted with an appalling misunderstanding of the relationship between leverage and diplomacy. History has shown that diplomacy, the practice of influencing the conduct of a foreign entity through negotiations, without leverage, the "action or advantage" of applying pressure on an object (e.g. using a lever in the most instrumental sense of the term), tends not to go very far.

But that's not how Biden's advisers — many of them holdovers from the Obama administration — see it. By their reckoning, leverage is something that angers adversaries and sows mistrust of American intentions. If you want to turn over a new leaf with the angry and mistrustful, the reasoning goes, you have to build confidence by giving something for nothing.

History has shown that diplomacy without leverage tends not to go very far. |

An early sign of this thinking came with the administration's decision in February to announce the withdrawal of U.S. support for the Saudi war effort in Yemen and to unconditionally reverse the Trump administration's designation of the Iranian-backed Yemeni group Ansar Allah (more commonly known as the Houthis) as a terrorist organization. The apparent reasoning for these decisions was that they would demonstrate goodwill amid U.S. efforts to broker a ceasefire in Yemen and pave the way for negotiating a new nuclear deal with Tehran.

Presumably the administration expected that Iran and its Houthi proxies would reciprocate for the unilateral concession by changing their conduct for the better. But the opposite happened. Houthi rebels responded by launching a major ground offensive in Marib province and stepping up their missile attacks on Saudi Arabia, while Iran's nuclear provocations continued unabated.

Much the same thinking appeared to underlie Secretary of State Antony Blinken's April 7 announcement of plans to "restart" aid to the Palestinians with a package of at least $235 million aimed at "provid[ing] critical relief to those in great need, foster[ing] economic development, and support[ing] Israeli-Palestinian understanding, security coordination and stability.... as a means to advance towards a negotiated two-state solution."

The ostensible reasoning behind the Biden administration's ending of its predecessor's moratorium on aid to the Palestinians mirrors its Yemen strategy. Palestinians didn't much like the aid cutoff, and the United States needs to entice them to end their unwavering refusal to accept the legitimacy of Israel as a Jewish state, the main sticking point in past U.S. efforts to broker an Israeli–Palestinian peace settlement.

Lavishing the Palestinians with aid in hopes of easing their rejectionism hasn't worked in the past. The Obama administration, which increased annual aid to a whopping $600 million, never succeeded in convincing Palestinian leaders to even meet with their Israeli counterparts, let alone make serious compromises. Providing aid and assistance without demanding major concessions in return emboldened and hardened the Palestinian position back then, and the same thing happened this time around — weeks later, Palestinians and Israelis were at war again.

Providing sanctions relief to the Iranians isn't going to entice them to compromise. |

Providing sanctions relief to the Iranians isn't going to entice them to compromise their nuclear ambitions or roll back their burgeoning ballistic missiles program or support for terrorist groups across the Middle East. Like Palestinian leaders, they surely appreciate what Biden has done for them, but believe they are better off pocketing the gifts and continuing their rejectionism. Both have good reason to believe that the Biden administration won't reverse its decision without new provocations on their part.

Biden must demonstrate that the days of getting something for nothing are over. |

The objective of diplomacy is to convince an adversary that it is better off conceding what is demanded. Biden does not need to demonstrate goodwill to Palestinian or Iranian leaders in order to do this — they already recognize that he is far more sympathetic to their position than his predecessor. If anything, it's imperative that he demonstrate that his goodwill has limits and that the days of getting something for nothing are over.

Gary C. Gambill is general editor at the Middle East Forum. Follow him on Twitter and Facebook.

Gregg Roman is director of the Middle East Forum. Follow him on Twitter and Facebook.