Republican candidates have largely ignored the Obama administration's failures in Syria. |

Given Syria's transformation in just a few years from one of the Arab world's most politically stable countries into a cauldron of mass ethno-sectarian bloodletting that ISIS calls home, you'd think it would take center stage in the Republican race for the White House.

Although plenty of places have taken a turn for the worse during President Obama's tenure as leader of the free world, nowhere has the deterioration been as stark – or as damaging to American interests – as in Syria. And this despite his administration's ostensible determination from the outset to bring an end to the bloodletting, his relatively close contact with the foreign governments fuelling the violence, and the fact that other Western governments have largely deferred to Washington. If anyone should be called to account for the international community's mishandling of Syria, it is President Obama.

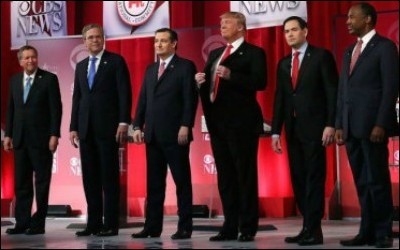

And yet Republican candidates have barely mentioned the country (just six times in the last two debates), and then only incidentally in boilerplate pledges to go after ISIS and do something about refugees. The resounding failure of administration efforts to stop Syria's disintegration has been virtually ignored.

Part of the reason Obama's Syria policy is off the table is that Republicans can't agree on what's wrong with it. Mainstreamers like Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) say he hasn't intervened enough to help Sunni Arab rebels oust the Iranian-backed Alawite-led regime of Bashar Assad, while a vocal minority of libertarians and tea-partiers, notably Sens. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) and Ted Cruz (R-Texas), say he has intervened too much on their behalf. The RNC and conservative media aren't particularly eager to draw attention to a problem for which the Republican Party has no clear answer.

Whatever the merits of full-on intervention vs. non-intervention, Obama's middling path is worse than either. |

But it's not just lack of consensus that accounts for this silence. Proponents of both positions tend to assume a linear relationship between American intervention and payoffs, which makes the Obama administration's policy second best for each (i.e. if a lot of intervention is best, then a little is better than none at all; if no intervention is best, then a little is better than a lot).

But this is a fallacy. Whatever the merits of full-fledged intervention vs. strict non-intervention, the Obama administration's middling path may well be much worse than either.

In a nutshell, the argument for intervention is that it would bring the central axis of the conflict – that between Assad and Sunni rebels – to a close sooner, sap jihadist strength by offering the Sunni population credible "moderate" alternatives, and cultivate pro-American goodwill in Syria.

Anti-interventionists have argued that heavy American involvement in the Syrian civil war would provoke greater involvement by Russia and Iran, discourage regional Sunni governments from stepping up to the plate in the fight against Iranian influence, and saddle the United States with responsibility for what comes next in Syria.

Obama's middle road – gradually increasing modest levels of aid in fits and starts, while talking tough and drawing illusory red lines – is producing none of the benefits and most of the drawbacks of full-on American support for the rebels. U.S. material support has been far too miniscule to impact the situation on the ground, draw recruits away from ISIS, or win the loyalty of combatants.

Obama's middle road is producing none of the benefits and most of the drawbacks of full-on American support for the rebels. |

At the same time, the administration's steadily (if slowly) increasing aid and vocal endorsement of rebel aims over the past three years have given the Arab states and Turkey false hope that we'll eventually do the job for them, leading to free-riding and other sorts of underhandedness (e.g. funding and arming militias with an eye toward gaining influence within the insurgency rather than toppling Assad).

So if this middle path is so bad, why has the Obama administration taken it? Superpowers aren't known for low-balling material aid to proxies they vocally support.

Ostensibly, this unusual approach is rooted in the belief that stalemate is more conducive to brokering a diplomatic settlement than facilitating major rebel advances. The supposed aim has been to provide just enough rebel aid that Assad and his sponsors would appreciate the necessity of a negotiated solution, but without enabling the rebels to achieve their aims without talking. Belated American airstrikes against ISIS targets in Syria have been calibrated not to tip the broader balance of forces there.

But it's doubtful anyone in the administration ever really believed this approach would bring peace to Syria, certainly not in the wake of Russia's military intervention last fall.

The real reason for the middle path is the Obama administration's effort over the past three years to square the circle between its pursuit of Israeli-Palestinian peace (for which it needed the goodwill of Sunni Arab governments and Turkey) and its pursuit of a negotiated solution to the Iranian nuclear threat (which might have been jeopardized by full-on support for the rebels).

That both exhaustive efforts failed spectacularly is bad enough. That nearly 300,000 Syrians have paid the ultimate price for Obama's pursuit of pie-in-the-sky "legacy" achievements is shameful. Republicans should start saying so.

Gary C. Gambill is a research fellow at the Middle East Forum